Head injuries are among the most critical medical emergencies, often leading to life-threatening complications such as epidural hematoma and subdural hematoma. These conditions involve bleeding around the brain, causing pressure that can impair brain function or result in death if untreated. While both are serious, they differ significantly in their causes, symptoms, progression, diagnosis, and treatment. As a board-certified neurosurgeon with expertise in SEO and content writing, I’ve created this comprehensive, reader-friendly guide to help you understand the nuances of epidural and subdural hematomas, empowering you to recognize warning signs and seek timely medical intervention.

This guide is structured for clarity, with detailed sections, subheadings, and bullet points to enhance readability, ensuring you can easily navigate the content. Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or medical enthusiast, this article provides actionable insights backed by medical expertise.

Understanding Hematomas: The Basics

A hematoma is a localized collection of blood outside blood vessels, typically caused by trauma or injury. In the brain, hematomas are particularly dangerous because the skull is a rigid structure, leaving little room for blood to accumulate without compressing vital brain tissue. This increased intracranial pressure (ICP) can disrupt brain function, leading to symptoms like confusion, seizures, or loss of consciousness.

Epidural and subdural hematomas are two types of intracranial hematomas, meaning they occur within the skull. They are distinguished by their location relative to the brain’s protective layers, known as the meninges (dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater). Understanding their differences is critical for timely diagnosis and treatment

Epidural Hematoma: A Detailed Overview

An epidural hematoma (EDH) occurs when blood collects between the inner surface of the skull and the dura mater, the tough, outermost layer of the meninges. This condition is typically associated with high-impact trauma and arterial bleeding, making it a rapidly progressing emergency.

Causes of Epidural Hematoma

Epidural hematomas are most often caused by:

- Traumatic Head Injury: High-energy impacts from motor vehicle accidents, falls from height, sports injuries (e.g., football, boxing), or assaults.

- Skull Fractures: Approximately 75–90% of epidural hematomas are associated with a skull fracture, which tears an artery, most commonly the middle meningeal artery.

- Non-Traumatic Causes (Rare): Bleeding disorders (e.g., hemophilia), anticoagulant therapy, or vascular malformations like arteriovenous malformations (AVMs).

Symptoms of Epidural Hematoma

Due to the arterial nature of the bleeding, symptoms often develop within hours of injury, progressing rapidly. A hallmark feature is the lucid interval, where a patient regains consciousness briefly before deteriorating. Common symptoms include:

- Loss of Consciousness: Brief unconsciousness at the time of injury, followed by alertness, then worsening symptoms.

- Severe Headache: Intense, localized pain that escalates quickly.

- Neurological Deficits: Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (hemiparesis), difficulty speaking (aphasia), or vision changes.

- Dilated Pupil: Often on the same side as the hematoma, indicating brain compression (a critical sign).

- Seizures: Sudden, uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Due to rising intracranial pressure.

- Confusion or Agitation: As pressure affects brain function.

Risk Factors

- Young Adults: More common in individuals under 40 due to higher participation in high-risk activities.

- Contact Sports: Football, hockey, or wrestling increase the risk of head trauma.

- Lack of Protective Gear: Not wearing helmets during biking, motorcycling, or construction work.

Diagnosis

Prompt diagnosis is critical for survival. Diagnostic tools include:

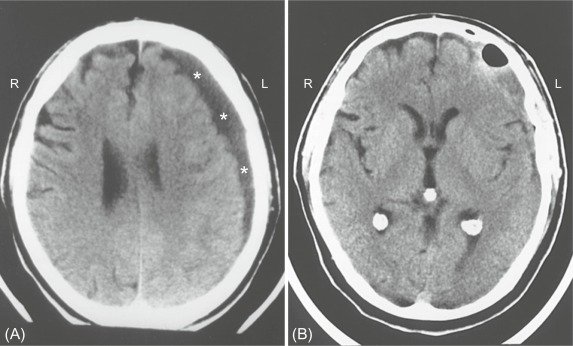

- CT Scan: The primary imaging modality, revealing a biconvex (lens-shaped) blood collection on the brain’s surface, characteristic of EDH.

- Neurological Examination: Assesses level of consciousness (using the Glasgow Coma Scale), pupil response, and motor function.

- Medical History: Details of the injury (e.g., timing, mechanism) guide diagnosis.

- X-Ray (if needed): To confirm skull fractures.

Treatment

Epidural hematomas are medical emergencies requiring immediate intervention to prevent brain herniation or death:

- Surgical Evacuation:

- Craniotomy: A section of the skull is temporarily removed to access and remove the hematoma, stop bleeding, and repair damaged vessels.

- Burr Hole Surgery: In urgent cases, small holes are drilled into the skull to drain blood and relieve pressure.

- Supportive Care:

- Anti-Seizure Medications: Drugs like levetiracetam or phenytoin to prevent seizures.

- Osmotic Diuretics: Mannitol or hypertonic saline to reduce brain swelling.

- Intensive Care Monitoring: Continuous assessment of neurological status and vital signs in an ICU.

- Post-Surgical Rehabilitation: Physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy to address deficits.

Prognosis

- With Prompt Treatment: Outcomes are often excellent, with many patients recovering fully if surgery occurs within hours.

- Delays in Treatment: Can lead to permanent brain damage, coma, or death due to rapid pressure buildup.

- Factors Affecting Recovery: Age, overall health, and the extent of brain compression.

Subdural Hematoma: A Detailed Overview

A subdural hematoma (SDH) occurs when blood collects between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater, the middle meningeal layer. It is typically caused by venous bleeding, often from torn bridging veins that connect the brain to the dura. SDHs can develop acutely or chronically, depending on the injury’s severity and the patient’s risk factors.

Causes of Subdural Hematoma

- Trauma: Common causes include falls, motor vehicle accidents, or blunt trauma (e.g., assaults). In infants, SDH may result from shaken baby syndrome.

- Spontaneous Bleeding: Seen in patients with:

- Anticoagulant Use: Medications like warfarin or aspirin increase bleeding risk.

- Alcohol Abuse: Leads to liver dysfunction and impaired clotting.

- Bleeding Disorders: Hemophilia or thrombocytopenia.

- Brain Atrophy: In older adults, brain shrinkage stretches bridging veins, making them prone to tearing even with minor trauma.

Types of Subdural Hematoma

- Acute SDH: Develops within hours to days after significant trauma, often life-threatening.

- Subacute SDH: Symptoms appear days to weeks post-injury, with slower progression.

- Chronic SDH: Develops over weeks to months, common in the elderly or those with minor, repeated head injuries.

Symptoms of Subdural Hematoma

Symptoms vary by type and severity:

- Acute SDH:

- Severe headache, often diffuse.

- Loss of consciousness or fluctuating alertness.

- Hemiparesis or motor weakness on one side.

- Seizures or slurred speech.

- Nausea, vomiting, or confusion.

- Chronic SDH:

- Gradual headaches that persist or worsen.

- Cognitive decline, memory problems, or personality changes (often mistaken for dementia).

- Difficulty walking or frequent falls.

- Lethargy or excessive sleepiness.

- Subtle neurological deficits, like mild weakness.

- Common Across Types: Unequal pupil size, vision changes, or seizures.

Risk Factors

- Elderly: Brain atrophy increases vulnerability to chronic SDH.

- Anticoagulant Therapy: Common in patients with atrial fibrillation or clotting disorders.

- Alcoholism: Increases fall risk and impairs clotting.

- Infants: Susceptible to SDH from abuse or accidental trauma.

- Repeated Minor Injuries: Common in athletes or individuals with frequent head impacts.

Diagnosis

- CT Scan: Reveals a crescent-shaped blood collection along the brain’s surface, distinguishing SDH from EDH.

- MRI: Preferred for chronic SDH to detect older blood or smaller hematomas.

- Neurological Assessment: Evaluates cognitive function, motor skills, and reflexes.

- Coagulation Studies: To check for bleeding disorders or anticoagulant effects.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the hematoma’s size, type, and symptoms:

- Surgical Options:

- Craniotomy: Used for large or acute SDHs to remove blood and relieve pressure.

- Burr Hole Drainage: Common for chronic SDHs, involving small holes to drain blood, often under local anesthesia.

- Craniectomy (Rare): Removal of a larger skull portion for severe cases.

- Non-Surgical Management:

- Small, asymptomatic SDHs may be monitored with serial CT scans.

- Medications like corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) to reduce inflammation.

- Reversal of anticoagulants (e.g., vitamin K or prothrombin complex concentrate).

- Post-Treatment Care:

- Anti-seizure medications to prevent complications.

- Rehabilitation to restore motor or cognitive function.

- Regular follow-up imaging to detect recurrence.

Prognosis

- Acute SDH: Higher mortality (up to 50–60% in severe cases) due to rapid progression and brain damage.

- Chronic SDH: Better prognosis with timely treatment, though elderly patients may face prolonged recovery due to comorbidities.

- Recurrence Risk: Chronic SDHs may recur, requiring repeat drainage or additional surgery.

Epidural vs Subdural Hematoma: A Side-by-Side Comparison

| Aspect | Epidural Hematoma | Subdural Hematoma |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Between skull and dura mater | Between dura and arachnoid mater |

| Blood Source | Arterial (often middle meningeal artery) | Venous (bridging veins) |

| Primary Cause | High-impact trauma with skull fracture | Trauma, spontaneous in elderly or anticoagulated patients |

| Onset | Rapid (hours) | Acute (hours-days), subacute (days-weeks), or chronic (weeks-months) |

| CT Appearance | Biconvex (lens-shaped) | Crescent-shaped |

| Symptoms | Lucid interval, severe headache, dilated pupil | Headache, confusion, cognitive decline (chronic) |

| Typical Patients | Younger adults, athletes | Elderly, infants, anticoagulant users |

| Treatment | Urgent craniotomy or burr hole | Craniotomy, burr hole, or observation for small SDHs |

| Prognosis | Good with prompt surgery | Varies; worse for acute, better for chronic |

| Mortality Risk | High if untreated, lower with early surgery | High for acute SDH, lower for chronic with treatment |

Collaborative Care: Neurologists and Neurosurgeons

Epidural and subdural hematomas often require a team approach:

- Neurologist’s Role:

- Conducts initial neurological assessments and orders imaging (CT/MRI).

- Manages non-surgical cases with medications (e.g., anti-seizure drugs, corticosteroids).

- Oversees long-term recovery, including rehabilitation for cognitive or motor deficits.

- Neurosurgeon’s Role:

- Performs surgical interventions like craniotomy or burr hole drainage.

- Manages acute emergencies, such as rapid brain compression.

- Monitors post-operative recovery in the ICU.

- Case Example:

- A 65-year-old patient falls and develops a chronic SDH. A neurologist diagnoses the condition via CT scan and refers to a neurosurgeon for burr hole drainage. Post-surgery, the neurologist manages medications and rehabilitation.

Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies

Shared Risk Factors

- Head Trauma: Falls, accidents, or sports injuries.

- Alcohol Use: Increases fall risk and impairs clotting.

- Medical Conditions: Bleeding disorders or anticoagulant therapy.

Specific Risk Factors

- Epidural Hematoma: Younger age, high-impact activities, lack of helmets.

- Subdural Hematoma: Advanced age, brain atrophy, repeated minor injuries.

Prevention Tips

- Wear Protective Gear: Helmets for biking, motorcycling, or contact sports.

- Vehicle Safety: Use seat belts and proper car seats for children.

- Fall Prevention: Install grab bars, remove tripping hazards, and use non-slip mats for the elderly.

- Medication Management: Monitor anticoagulant therapy closely with a healthcare provider.

- Education: Raise awareness about head injury risks in sports or workplaces.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Attention

Both epidural and subdural hematomas can be life-threatening. Seek emergency care if you or someone experiences:

- Loss of Consciousness: Even brief, after a head injury.

- Worsening Headache: Persistent or escalating pain.

- Neurological Symptoms: Confusion, weakness, difficulty speaking, or seizures.

- Pupil Changes: Unequal pupil size or vision loss.

- Nausea/Vomiting: Especially after trauma.

- Chronic Symptoms: Gradual memory loss, personality changes, or difficulty walking (common in chronic SDH).

For non-emergent symptoms, consult a neurologist for a thorough evaluation. Early detection can prevent complications.

Small, asymptomatic hematomas (especially chronic SDHs) may be monitored with imaging and medications. However, larger or symptomatic hematomas typically require surgery.

Epidural Hematoma: Recovery may take weeks to months, depending on the extent of brain damage and the patient’s overall health.

Subdural Hematoma: Acute SDH recovery may take months, while chronic SDH patients often recover faster, especially with burr hole drainage.

Epidural and subdural hematomas are serious conditions that demand prompt recognition and treatment. Epidural hematomas are typically caused by arterial bleeding and progress rapidly, often requiring urgent surgery. Subdural hematomas, driven by venous bleeding, can range from acute to chronic, with varied symptoms and treatment needs. Understanding their differences—location, causes, symptoms, and management—is crucial for patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

If you or a loved one experiences symptoms of a head injury, don’t wait. Early intervention by a neurologist or neurosurgeon can be lifesaving. Contact our expert neurosurgery team for a consultation or download our free guide on head injury prevention and recovery.

Call to Action: Worried about head injury symptoms? Book an appointment with our board-certified neurosurgeons or request our comprehensive guide on brain health today.