A subdural hematoma (SDH) is a serious medical condition where blood accumulates between the brain and its outer protective layer, the dura mater, often due to head trauma or underlying health issues. This blood collection can compress the brain, leading to severe neurological symptoms or even life-threatening complications. When the hematoma is large, acute, or causes significant symptoms, a surgical procedure called a craniotomy may be necessary to remove the blood and relieve pressure. As a board-certified neurosurgeon, I’ve created this comprehensive, easy-to-read guide to provide an in-depth understanding of subdural hematoma craniotomy. This article covers the condition, the surgical process, recovery, risks, alternatives, and long-term care, structured with clear subheadings and bullet points to ensure clarity for patients, caregivers, and those seeking detailed medical knowledge.

What Is a Subdural Hematoma?

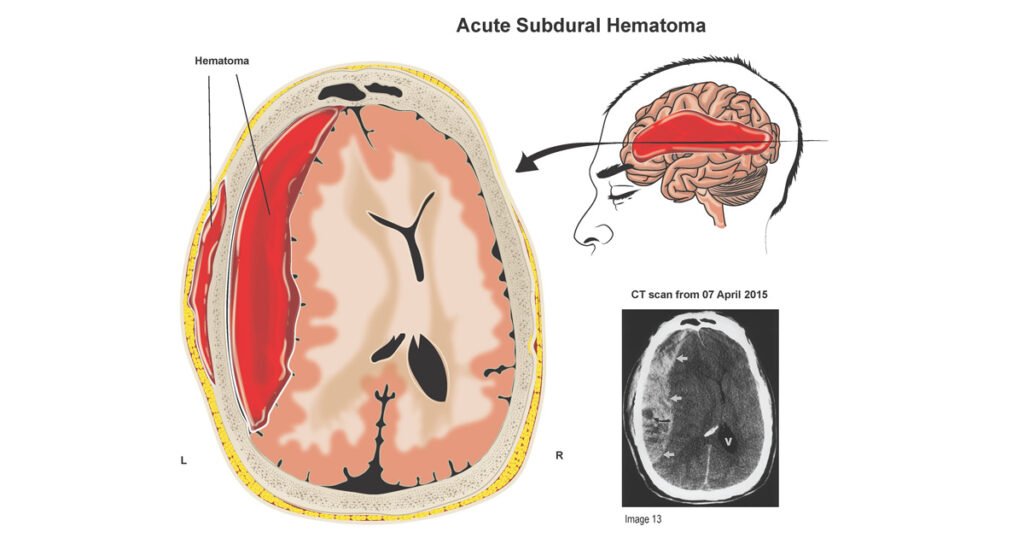

A subdural hematoma occurs when blood collects in the space between the dura mater (the tough, outermost membrane covering the brain) and the arachnoid mater (the delicate middle layer). This bleeding typically results from torn bridging veins, which are small veins connecting the brain’s surface to the dura. The accumulated blood forms a hematoma that presses on the brain, potentially impairing its function and causing a range of symptoms, from mild headaches to loss of consciousness.

Types of Subdural Hematoma

Subdural hematomas are classified based on the timing and speed of symptom onset:

- Acute Subdural Hematoma: Develops within hours to 1–2 days after a significant head injury, often caused by high-impact trauma. These are the most dangerous due to rapid progression and severe brain compression.

- Subacute Subdural Hematoma: Symptoms emerge days to weeks after the injury, with a slower buildup of blood that may cause less immediate but still serious effects.

- Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Develops over weeks to months, often after minor or repeated head injuries. This type is more common in older adults due to brain atrophy, which stretches bridging veins, making them prone to tearing.

Causes of Subdural Hematoma

- Head Trauma: The leading cause, including:

- Falls, especially in the elderly or infants.

- Motor vehicle accidents.

- Sports injuries (e.g., football, boxing, or hockey).

- Assaults or blunt trauma to the head.

- Spontaneous Bleeding: Occurs without obvious trauma in patients with:

- Anticoagulant Medications: Drugs like warfarin, aspirin, or direct oral anticoagulants (e.g., apixaban) increase bleeding risk.

- Alcohol Abuse: Chronic alcohol use impairs blood clotting and increases fall risk.

- Bleeding Disorders: Conditions like hemophilia or thrombocytopenia reduce the blood’s ability to clot.

- Brain Atrophy: In older adults, age-related brain shrinkage stretches bridging veins, making them more susceptible to rupture even with minor bumps.

- Shaken Baby Syndrome: A form of abusive head trauma in infants, leading to subdural bleeding.

Symptoms of Subdural Hematoma

Symptoms depend on the hematoma’s type, size, and location:

- Acute SDH:

- Severe, worsening headache.

- Loss of consciousness or fluctuating alertness.

- Seizures or uncontrolled muscle movements.

- Hemiparesis (weakness or paralysis on one side of the body).

- Difficulty speaking (aphasia) or slurred speech.

- Confusion, agitation, or disorientation.

- Chronic SDH:

- Persistent, gradually worsening headaches.

- Memory problems or cognitive decline, often mistaken for dementia in older adults.

- Personality changes, such as irritability or apathy.

- Difficulty walking, frequent falls, or poor balance.

- Lethargy or excessive sleepiness.

- Shared Symptoms:

- Nausea and vomiting due to increased intracranial pressure.

- Unequal pupil size (anisocoria), often indicating brain compression.

- Vision changes, such as blurriness or double vision.

- Dizziness or loss of coordination.

Why a Craniotomy May Be Necessary

A craniotomy is indicated when a subdural hematoma causes significant brain compression or severe symptoms that threaten life or neurological function. Specific scenarios include:

- Large hematomas (typically >1 cm thick on imaging) causing brain shift or herniation.

- Acute SDHs with rapid symptom progression, such as loss of consciousness or seizures.

- Chronic SDHs with thick, clotted blood or membranes that cannot be drained with less invasive methods.

- Failure of conservative treatments or recurrence after less invasive procedures like burr hole drainage.

What Is a Subdural Hematoma Craniotomy?

A craniotomy is a surgical procedure in which a neurosurgeon removes a portion of the skull (called a bone flap) to access the brain, evacuate the hematoma, and stop any active bleeding. For subdural hematomas, this procedure allows direct visualization and removal of blood clots, relief of brain pressure, and repair of damaged blood vessels. It is typically reserved for complex or acute cases where less invasive options are insufficient.

Types of Craniotomy for Subdural Hematoma

- Standard Craniotomy: Involves removing a larger bone flap (3–5 inches in diameter) to access extensive or clotted hematomas, common in acute SDHs.

- Mini-Craniotomy: Uses a smaller incision and bone flap for less extensive hematomas, reducing recovery time while still addressing significant bleeding.

- Decompressive Craniectomy (Rare): The bone flap is not immediately replaced, allowing the brain to swell without constraint in cases of severe intracranial pressure. The flap is later replaced in a separate surgery.

The Craniotomy Procedure: A Detailed Look

A subdural hematoma craniotomy is a highly specialized procedure performed in a neurosurgical operating room under general anesthesia. Below is a step-by-step explanation of the process, designed to demystify the surgery for patients and families.

1. Pre-Surgical Preparation

- Diagnostic Imaging:

- CT Scan: The primary tool, showing a crescent-shaped hematoma along the brain’s surface, its size, location, and effect on brain structures (e.g., midline shift).

- MRI: Used for chronic SDHs or to assess underlying brain damage, offering detailed views of older blood or tissue injury.

- Neurological Examination: Assesses:

- Level of consciousness using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which scores eye, verbal, and motor responses (3–15 points).

- Pupil size and reactivity to detect brain compression.

- Motor function, reflexes, and speech to identify deficits.

- Medical Evaluation:

- Blood tests to check clotting parameters (e.g., INR, platelet count), critical for patients on anticoagulants.

- Assessment of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) to optimize surgical safety.

- Anticoagulant Reversal: For patients on blood thinners, medications like vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or prothrombin complex concentrate are used to restore normal clotting.

- Patient Counseling: The neurosurgeon explains the procedure, risks, benefits, and alternatives, obtaining informed consent.

- Pre-Operative Measures: Shaving a small area of the scalp, administering antibiotics to prevent infection, and preparing the patient for anesthesia.

2. Surgical Procedure

- Anesthesia: General anesthesia is administered to ensure the patient is unconscious and pain-free throughout the surgery.

- Head Positioning: The patient’s head is secured in a three-pin fixation device to prevent movement and allow precise surgical access.

- Scalp Incision:

- A curved incision is made over the hematoma site, guided by CT or MRI findings.

- The scalp is carefully retracted to expose the skull.

- Bone Flap Removal:

- Using a high-speed drill and specialized saw, the neurosurgeon creates a bone flap, typically 3–5 inches in diameter.

- The flap is lifted and stored sterilely for later replacement.

- Dura Opening:

- The dura mater is carefully incised to expose the hematoma.

- The neurosurgeon works meticulously to avoid damaging underlying brain tissue.

- Hematoma Evacuation:

- Liquid blood is suctioned using a gentle vacuum device.

- Solid clots are removed with specialized instruments.

- The surgical field is irrigated with saline to clear residual blood and ensure visibility.

- Bleeding Control:

- Torn bridging veins or other bleeding sources are identified and cauterized (using electrocautery) or ligated with sutures.

- Hemostatic agents (e.g., Surgicel) may be applied to promote clotting.

- Brain Protection:

- The brain is handled with extreme care to minimize trauma.

- Saline irrigation keeps the surgical field clean and prevents drying of brain tissue.

- Closure:

- The dura is sutured closed, sometimes with a synthetic patch if it cannot be fully approximated.

- The bone flap is replaced and secured with titanium plates, screws, or wires.

- The scalp is closed with sutures or surgical staples, and a sterile dressing is applied.

3. Duration

- The procedure typically takes 2–5 hours, depending on:

- The hematoma’s size and complexity (e.g., clotted vs. liquid blood).

- The presence of additional complications, such as brain swelling or multiple bleeding sites.

- The need for additional procedures, like repairing a skull fracture.

4. Immediate Post-Surgical Care

- Intensive Care Unit (ICU): Patients are transferred to the ICU for 1–3 days, where they are monitored for:

- Neurological status (consciousness, pupil response, motor function).

- Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen levels).

- Intracranial pressure, if a monitoring device is placed.

- Medications:

- Anti-Seizure Drugs: Levetiracetam, phenytoin, or valproate to prevent post-operative seizures, which occur in up to 20% of patients.

- Pain Relief: Analgesics like acetaminophen or low-dose opioids for surgical site discomfort.

- Steroids: Dexamethasone to reduce brain swelling, if indicated.

- Antibiotics: To prevent infection at the surgical site.

- Imaging: A post-operative CT scan within 24–48 hours confirms complete hematoma removal and checks for complications like re-bleeding or swelling.

Recovery After Subdural Hematoma Craniotomy

Recovery from a craniotomy is a gradual process, influenced by the hematoma’s type, the patient’s age, and overall health. Below is a detailed timeline and what to expect.

Immediate Post-Operative Period (1–7 Days)

- Hospital Stay: Typically 3–10 days, with 1–3 days in the ICU for close monitoring.

- Neurological Monitoring: Regular checks of consciousness, speech, and motor function to detect complications like re-bleeding or swelling.

- Activity Restrictions:

- Patients remain on bed rest initially, with gradual mobilization (e.g., sitting, standing) under nursing supervision.

- Avoid coughing, straining, or sudden movements to prevent pressure spikes.

- Wound Care: The surgical site is kept clean and dry to prevent infection. Dressings are changed regularly.

- Symptom Management: Pain, nausea, or swelling is managed with medications.

Short-Term Recovery (1–4 Weeks)

- Discharge: Most patients return home within 3–10 days, depending on their condition and support system.

- Follow-Up Visits: Weekly appointments to:

- Monitor neurological recovery.

- Remove sutures or staples (7–14 days post-surgery).

- Adjust medications (e.g., tapering steroids or continuing anti-seizure drugs).

- Rehabilitation:

- Physical Therapy: To improve strength, balance, and coordination, especially if hemiparesis or falls were present.

- Occupational Therapy: To regain daily living skills, like dressing or eating.

- Speech Therapy: For patients with speech or swallowing difficulties.

- Activity Guidelines:

- Avoid heavy lifting, strenuous exercise, or contact sports for at least 4–6 weeks.

- Gradual return to light activities, like walking, as approved by the neurosurgeon.

Long-Term Recovery (1–6 Months)

- Return to Normal Activities:

- Most patients resume work, driving, or daily routines within 6–12 weeks, depending on the hematoma’s severity and individual progress.

- Patients with acute SDHs or significant brain damage may require longer recovery.

- Cognitive and Motor Recovery:

- Some patients experience lingering issues, such as memory difficulties, concentration problems, or mild weakness.

- Ongoing rehabilitation can significantly improve these deficits.

- Follow-Up Imaging: CT or MRI scans at 1, 3, or 6 months to monitor for recurrence or residual effects.

- Medication Management: Anti-seizure drugs are typically continued for 3–6 months, with discontinuation based on neurologist evaluation.

Factors Influencing Recovery

- Age: Elderly patients (over 65) may recover more slowly due to brain atrophy, comorbidities, or reduced healing capacity.

- Hematoma Type: Acute SDH patients face longer, more complex recoveries than chronic SDH patients, who often respond well to surgery.

- Pre-Existing Conditions: Diabetes, hypertension, or anticoagulant use can delay healing or increase complication risks.

- Extent of Brain Damage: Severe compression or delays in treatment may lead to permanent deficits.

Risks and Complications of Craniotomy

Craniotomy is a major surgery with potential risks, though these are minimized by an experienced neurosurgical team and modern techniques. Common risks include:

- Infection:

- Superficial (scalp or bone flap) or deep (meningitis, brain abscess).

- Treated with antibiotics or, rarely, additional surgery.

- Re-Bleeding:

- Recurrence of the hematoma (10–20% risk, especially in chronic SDHs).

- May require repeat surgery or alternative treatments.

- Seizures:

- Occur in 10–20% of patients post-craniotomy.

- Managed with anti-seizure medications, which are often continued prophylactically.

- Brain Swelling:

- Can increase intracranial pressure, requiring steroids or decompressive craniectomy.

- Neurological Deficits:

- Temporary or permanent issues with speech, memory, movement, or vision.

- Rehabilitation can mitigate these effects.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Leak:

- Rare but may occur if the dura is not fully sealed.

- May require surgical repair or temporary drainage.

- Anesthesia Complications:

- Rare risks include allergic reactions, breathing difficulties, or cardiovascular issues.

- Blood Clots:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism due to immobility post-surgery.

- Prevented with compression stockings or blood thinners (once bleeding risk is low).

Patients are closely monitored to detect and address complications early, improving outcomes.

Alternatives to Craniotomy

While craniotomy is effective for large or complex subdural hematomas, less invasive or non-surgical options may be considered based on the hematoma’s characteristics:

- Burr Hole Drainage:

- Involves drilling one or two small holes (1–2 cm) in the skull to drain liquid blood.

- Preferred for chronic SDHs or smaller acute SDHs with mostly liquid blood.

- Performed under local or general anesthesia, with faster recovery than craniotomy.

- Less effective for thick, clotted hematomas or cases with significant brain compression.

- Non-Surgical Management:

- Small, asymptomatic SDHs (e.g., <1 cm thick with no neurological symptoms) may be monitored with:

- Serial CT or MRI scans to track hematoma size.

- Medications like corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) to reduce inflammation.

- Suitable for patients with high surgical risks or minimal symptoms.

- Small, asymptomatic SDHs (e.g., <1 cm thick with no neurological symptoms) may be monitored with:

- Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization:

- An emerging, minimally invasive procedure where the middle meningeal artery (a potential blood source for chronic SDHs) is blocked using catheters and embolic agents.

- Reduces recurrence risk, particularly for chronic SDHs.

- Performed in specialized centers and not yet widely available.

- Conservative Management:

- For patients on anticoagulants, reversal agents (e.g., vitamin K) and close monitoring may stabilize small hematomas without surgery.

- Includes bed rest, hydration, and symptom management.

The neurosurgeon evaluates imaging, symptoms, and patient health to determine the best approach.

Collaborative Care: The Medical Team

Managing a subdural hematoma craniotomy requires a multidisciplinary team:

- Neurologist:

- Diagnoses the hematoma through imaging and neurological exams.

- Manages non-surgical cases or post-operative medications (e.g., anti-seizure drugs).

- Oversees long-term recovery, including cognitive or motor rehabilitation.

- Neurosurgeon:

- Performs the craniotomy and manages intraoperative complications.

- Monitors post-surgical recovery and coordinates follow-up care.

- Neurocritical Care Team:

- Provides ICU monitoring for vital signs, intracranial pressure, and neurological status.

- Manages complications like seizures or swelling.

- Rehabilitation Specialists:

- Physical Therapists: Improve strength, balance, and mobility.

- Occupational Therapists: Restore daily living skills.

- Speech Therapists: Address speech, swallowing, or cognitive issues.

- Nurses and Pharmacists: Administer medications, monitor wounds, and educate patients on post-operative care.

- Case Example: A 60-year-old patient with an acute SDH from a car accident undergoes a CT scan ordered by a neurologist, confirming a large hematoma. A neurosurgeon performs a craniotomy, and the neurocritical care team monitors the patient in the ICU. Post-discharge, rehabilitation specialists and the neurologist manage recovery.

Preventing Subdural Hematomas

While not all subdural hematomas are preventable, the following strategies can reduce risk:

- Protective Gear:

- Wear helmets during sports (e.g., football, cycling), motorcycling, or construction work.

- Use head protection in high-risk occupations.

- Vehicle Safety:

- Always wear seat belts and ensure children use appropriate car seats or booster seats.

- Follow traffic safety rules to avoid accidents.

- Fall Prevention (Especially for the Elderly):

- Install grab bars in bathrooms and stairways.

- Use non-slip mats and ensure adequate lighting.

- Remove tripping hazards like loose rugs or clutter.

- Encourage balance exercises or physical therapy to improve stability.

- Medication Management:

- Patients on anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, apixaban) should have regular blood tests and follow medical advice to minimize bleeding risk.

- Discuss alternatives with a doctor if fall risk is high.

- Limit Alcohol Consumption:

- Reduces fall risk and improves blood clotting function.

- Education and Awareness:

- Educate families about head injury risks, especially for infants (e.g., avoiding shaking) and the elderly.

- Recognize early symptoms like persistent headaches or confusion to seek timely care.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Subdural hematomas can be life-threatening, and early intervention is critical. Seek emergency care if you or someone experiences:

- Post-Trauma Symptoms:

- Loss of consciousness, even briefly, after a head injury.

- Severe or worsening headache.

- Seizures, vomiting, or confusion.

- Neurological Signs:

- Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body.

- Slurred speech or difficulty speaking.

- Unequal pupil size or vision changes.

- Chronic Symptoms (Especially in the Elderly):

- Persistent headaches lasting days or weeks.

- Memory problems, personality changes, or cognitive decline.

- Difficulty walking, frequent falls, or lethargy.

For non-emergent symptoms, contact a neurologist or neurosurgeon for a thorough evaluation, including imaging and neurological testing.

A subdural hematoma craniotomy is a critical procedure that can save lives and prevent permanent brain damage in patients with significant subdural hematomas. By removing blood and relieving pressure on the brain, this surgery addresses acute and complex cases that less invasive methods cannot manage. Understanding the condition, the surgical process, recovery expectations, and potential risks empowers patients and families to make informed decisions and seek timely care. If you or a loved one experiences symptoms of a head injury—such as severe headaches, confusion, or seizures—act quickly to consult a neurologist or neurosurgeon. Early diagnosis and intervention are key to optimal outcomes.